Back in May of 2021, I participated in my first live-in-person-post-Covid art exhibition. It was the Oddities Bazaar in Denver, PA (near Adamstown which is near Reading). The show was great – at the famous Renninger’s Antiques Mall - but that’s not the point of this blog. The point is a graveyard.

I’ve traveled quite a bit across the U.S. (and a bit in Italy) over the ten-plus years that I’ve been writing this blog, but COVID put a stop to travel for awhile, didn’t it? During that period I drove around the tri-state area near Philadelphia, where I live, but that was it. Adamstown was an unusual trip for me, only about an hour and a half due west, but still, farther than I’d gone in about 16 months. As I write this in November 2021, travel bans and lockdowns are pretty much a thing of the past. Its no longer unusual to see planes in the sky.

On that day back in May, I got to Renninger’s about 8 a.m., half an hour before setup. So of course, I grabbed my smart phone, hit the Google Maps app, and typed in “cemetery nearby.” Finding hidden gems was never this easy! (By the way, if you try this, you will get different results if you type in “graveyard nearby.” Go figure.)

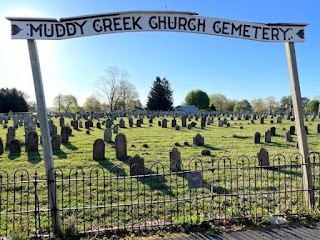

So, up pops “Muddy Creek Church Cemetery,” no more than half a mile away. Great name! (If you go, the address is 11 S Muddy Creek Rd, Denver, PA 17517.) Shot over there to find the superb sign you see above. Also, the Muddy Creek Church is across the street. It’s a fairly large cemetery, with rolling hills and a central driveway – a few acres. To the right of the entrance are Victorian-era and newer grave stones, to the left are older ones, dating back to around 1730, when the cemetery was established. It was these older stones that caught my attention.

From the road, just beyond the cemetery sign, were dozens of large brownstone gravemarkers, the kind I’ve seen carved with angel heads in North Jersey. This early in the morning, I could only see their plain backs. They were in shadow, but the other side of the stones – and whatever might be inscribed on them – were brightly lit by the morning sun.

|

| Muddy Creek Lutheran Church in background |

I drove into the cemetery from the newer entrance up the road, parked my vehicle as close to the old stones as possible, and got out to stretch my legs. Had about twenty minutes before I had to get over to Renninger’s to start setting up my photography, cards, books, and other items to exhibit and sell. As I walked up the hill, I noted a few really interesting marble-arched gravemarkers, the type of which I’ve only seen around the Pottstown, PA area.

When I got to the brownstone markers, I was stunned! Looking at me from several stones were life-sized faces carved in bas-relief into the stone! I would guess these are likenesses of the deceased. I’ve never seen this anywhere else. I’ve seen some wonderful brownstone carvings of angels and winged death’s heads here and there, but I’ve never seen anything like this in brownstone! Was it a Pennsylvania Dutch or Amish thing to do? Some neighboring stones had floral design carvings, which reminded me of Amish quilts.

But these plain folk are not into embellishment, right? Sort of like Quakers, with their simple flush-to-the-ground grass markers? Well, that may be the case with Amish gravemarkers, the Amish being a religious denomination (along with Mennonites, etc.) that falls under the “Pennsylvania Dutch” umbrella term. Some of these Pennsylvania Germans, however, who emigrated to Pennsylvania during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries developed a highly artistic folk art called Fraktur, so named after the distinctive font style (see link http://frakturweb.org/). Most Fraktur art was created between 1740 and 1860.

The floral carvings on these stones at Muddy Creek seem to be examples of Fraktur folk art, though I am certainly no expert. All names and dates on these stones have been worn away, but the faces, the designs, the feelings remain. Certainly, the wilting flowers became a common, Victorian-era symbol of a life lost, a popular form of mourning art. Turns out I was wrong about these seemingly “simple people” – PA Dutch Fraktur folk art, popular in the early to late 1800s, was highly artistic, colorful, and used to adorn (and therefore closely associated with) rites of social life e.g. birth and marriage. Examples of the documents used to certify such events can be seen here http://frakturweb.org/what-is-fraktur/fraktur-gallery/. Death being a part of life, it makes sense that the Fraktur artistic style would be used to adorn their gravestones.

Mary Roach, in her book, SPOOK, says that readers assume that “authors are experts in the field about which they have chosen to write.” She offers that “Possibly I’m the only one who begins a project from a state of near absolute ignorance.” Well, no, she’s not the only one, LOL. Pretty much describes my approach as well, so I am asking for my readers to help me out! I’ve done a bit of research after the fact, but the faces still baffle me. I’m thinking they were prominent citizens of the area, since they would be the ones with the money to have such a memorial stone carved. It is fairly common to see faces, busts, and even entire bodies sculpted in granite in the Victorian era, but these brownstones seem to have been made prior to that time.Offering a clue to the area’s history is this plaque on the cemetery fence, designating it as “Cocalico Area Historical Site.” According to the East Cocalico Township website, “The name Cocalico is believed to have originated from "koch hale kung", Delware Indian words meaning "den of serpents", apparently referring to the abundance of snakes near the creek at that time,” (the area being settled around 1723). Hmmmm….glad I didn’t wander off into the woods looking for the actual Muddy Creek. (https://www.eastcocalicotownship.com/about-your-township/pages/township-history)New England boasts many fine examples of slate stones carved with a likeness of the deceased, and I’m wondering if any of my readers have seen the brownstone versions anywhere else, like these in Muddy Creek? I put their creation age around 1830, as that seems to be the death dates on the marble stones nearby, on which some inscription is still visible. The faces on these stones are not soul effigies, i.e., angel-winged head carvings, but, I believe, the likenesses of the actual deceased person.

As I was wondering if anyone could shed light on this Muddy Creek Mystery, I happened on a couple recent Instagram posts by @deaths_heads_and_angels (the artist who also goes by the name of @phil_odendron and has become a personal friend over the past few months). He has published images of brownstone gravemarkers in this same geographic region of Pennsylvania, with folk art embellishments of the type I saw. His are mainly soul effigies, however – angelic death’s heads with wings, although he has found a few that do not appear to be skull-based, so they may be representations of the dearly departed (please visit his extraordinary collection of images at https://www.instagram.com/deaths_heads_and_angels/).

|

| Author with Muddy Creek headstone |

References and additional reading:

http://www.mclchurch.org/our-story.html

Fraktur Folk Art:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fraktur_(folk_art)

If you would like to browse my ETSY shop to see the kind of work I had for sale at Renninger’s, please visit here:

https://www.etsy.com/shop/StoneAngels